The rising political forces in Brazil seek bridges that will allow them to unlock the secret of how a declining nation can rise again.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

The Brazilian local elections, whose first round took place on October 6, are important as predictive elements of the country’s main political trends. There is a partial correspondence between the results of these municipal-level elections and the electoral outcomes that may be found in the general elections, which are always held two years later.

In the case of these 2024 elections, it can be said that they indeed confirm trends from the 2022 general elections and already allow possible patterns for 2026 to be deduced.

First of all, the most obvious political-electoral phenomenon of the local elections is the unprecedented strengthening of the “Centrão” — the political center. It’s clear that the center has been decisive in Brazilian politics at least since the end of the military dictatorship, with centrist parties (led by the MDB [Brazilian Democratic Movement]) almost always acting as the “kingmaker” for all successive governments.

Centrist parties such as the PSD (Social Democratic Party), the MDB, the PP (Progressive Party), and other smaller ones will now command more than 55% of Brazilian cities, whereas until then they commanded approximately 45%, and 10 years ago the Centrão controlled approximately 40% of Brazilian cities.

But it is important to highlight a specific dimension of this Centrão rise. In the cities where this phenomenon occurred, the Centrão was almost always associated with the Bolsonaro-aligned right — or more specifically with what we could call the “pragmatic wing” of Bolsonarism, which today enjoys the support of Bolsonaro himself.

After being defeated in the 2022 general elections, Bolsonarism, which always had entropic and nihilistic tendencies, began to fragment and, in fact, split into at least two parts: an uncompromising (or even “schizophrenic”) Bolsonarism, prone to believing in conspiracy theories about a “communist threat” coming from Russia and China, heavily influenced by the late neoconservative thinker Olavo de Carvalho; and a pragmatic Bolsonarism (formerly rejected by Bolsonaro himself), willing to compromise, dialogue with centrist parties, and, on some occasions, even with the left in exchange for tangible political benefits.

It is this second sector of Bolsonarism that has been consolidating throughout 2023 and 2024 and has managed to build alliances in several cities with centrist forces, as was the case in São Paulo, where Mayor Ricardo Nunes, from the MDB, is being supported by Jair Bolsonaro in his re-election bid. In fact, in São Paulo, the second round will be contested between this alliance of the center and pragmatic Bolsonarism against the left-liberal candidate Guilherme Boulos, supported by President Lula. In third place in the first round was precisely a representative of this uncompromising Bolsonarism, Pablo Marçal.

In most Brazilian capitals, however, the left was absent from the fight for first place, with the majority of capitals contested between different sectors of the Centrão and the right — which, in addition to the factions of Bolsonarism, also includes the liberal right.

This liberal right has been represented in Brazil by the PSDB (Brazilian Social Democracy Party). Throughout the 1990s and the first decade of the new millennium, it was the PSDB that represented the “right-wing” of Brazilian liberal democracy. But in recent years, the PSDB has been shrinking, indicating even the possibility of disappearing, reinforced by this year’s local electoral results.

If in 2008 the PSDB seemed to be the second strongest party locally, commanding 776 cities, and the third strongest nationally, now the PSDB will govern only 273 cities. A first conclusion, therefore, is that the most important political forces of the first decades of the New Republic are in decline — both the liberal right and the liberal left are losing their ability to politically mobilize, as well as their protagonism. However, this is not entirely new. If in the 2002 elections the PT won the presidency for the first time with only one important alliance (the PL, in its pre-Bolsonaro era), by the 2022 elections, the PT needed the support of several other parties (PV, PSOL, PSB, Solidariedade, Avante, etc.), as well as the backing of mass media, the judiciary, the financial system, and other important actors.

In building the government, the PT, in turn, constructed a “broad front” that ranged from socialists to neoliberals, with the Centrão and the liberal right occupying several ministry and secretariat posts. The PT has thus become incapable of “standing on its own feet,” which has also been expressed in great difficulty in mobilizing the population and generating enthusiasm for its own agendas.

Naturally, it is a fact that the PT (Workers’ Party) gained some municipalities compared to 2020 (66, to be more specific), but if we compare with 2016, we still see a drop of 6 municipalities, and compared to 2012, it’s almost 400 fewer. But this analysis of the PT as an individual party is not enough; it’s necessary to see it in the context of the Brazilian left as a whole. In this field, only the PT and the PSB (Brazilian Socialist Party) grew in these local elections, and the PSB’s growth didn’t make up for its decline in previous years. Nonetheless, all other leftist parties in Brazil shrank: PDT (Democratic Labor Party), PCdoB (Communist Party of Brazil), PV (Green Party), and PSOL (Socialism and Liberty Party) have sunk dramatically and are practically at risk of disappearing.

What explains this overall collapse of the left with only marginal growth of the PT and PSB? First, the only way for the PT to grow outside major elections is by absorbing the smaller left-wing parties. It seems to have lost the ability to compete for centrist or apolitical votes. In this sense, the political landscape of the Brazilian left has become a zero-sum game.

The proof of this is that, over the past four years, the PT has managed to take several key politicians from smaller left-wing parties, like Marcelo Freixo in Rio de Janeiro. The parties that have lost the most votes are precisely those that lost the most activists and political leaders to the PT — and even then, the PT hasn’t managed to compensate for its own shrinkage in recent years.

For the PT, this is a significant crisis, even though the party now tends to project a sense of calm. If the party led by the most charismatic Brazilian leader of the past half-century cannot even stand on its own without “parasitizing” other parties, it’s a sign that it suffers from a severe condition that could prove terminal.

Let’s imagine the Brazilian political scenario after Lula’s passing (who, let’s remember, is already 78 years old…). The reality is that Lula hasn’t managed to create a political “heir” remotely similar to him. In fact, the PT itself is a party of constantly competing factions, unified, however, by Lula’s charismatic personality.

There will then be two possible paths for the PT: 1) survive and rebuild by absorbing these smaller left-wing parties that it is already trying to absorb; 2) disintegrate into 2 or 3 parties, as the bureaucratic leaders of the various factions seek to assert their own authority.

Simultaneously, as the PT absorbs members and militants from parties like PSOL and PCdoB, it is also undergoing a qualitative change. Beyond the differences between internal factions, the major internal “split” within the PT is generational: older militants, representing what we might call the “Old Left” (but already within the context of political liberalism, embraced by the PT since its founding), and the younger ones, belonging to the “New Left.” Generally speaking, if Lula is the greatest symbolic figure of the Brazilian “Old Left,” the smaller parties increasingly making up the PT (and the youth of the PT itself) belong hegemonically to the more liberal, progressive, and “European” sectors of the left.

Given this analysis of the electoral landscape and the near future, it is necessary to “present” Brazil’s political perspectives to the international actors that have been Brazil’s partners.

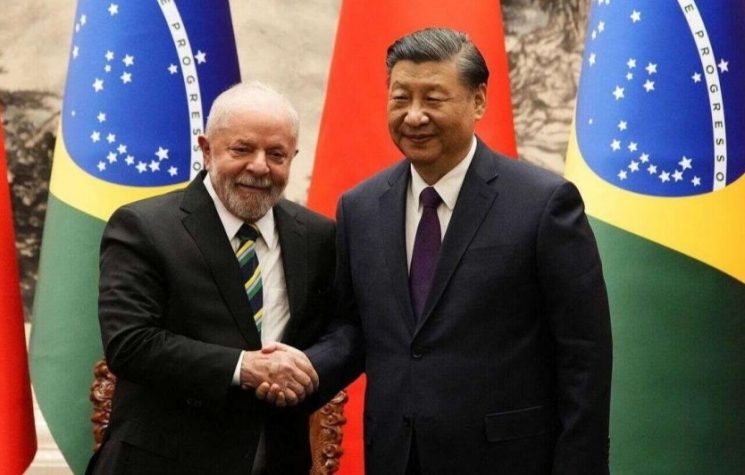

Here, we refer specifically to those countries that have expectations regarding Brazil in terms of counter-hegemonic processes of building a multipolar world order — countries that have been repeatedly baffled by some of Brazil’s “inexplicable” choices since Lula’s return.

It has been traditional for some important international geopolitical actors to bet on right-wing sovereigntist relations in Europe, while in the Ibero-American context, they bet on the anti-imperialist left. Cuba, Venezuela, and Nicaragua, to name a few, have been reliable partners, for example, of Russia, China, Iran, and Syria. Even in countries governed by forces aligned with Atlanticism or with unstable political landscapes, leftist parties have been important interlocutors for international counter-hegemonic sectors.

In Brazil’s case, however, this will become increasingly unlikely, both for quantitative and qualitative reasons. We’ve already explained them, but to recap: the left is shrinking and losing mobilization capacity in Brazil; much of the remaining Brazilian left has a pro-Western orientation due to a sense of “fraternity” supported by adherence to wokism. Young political leaders of the Brazilian left are mostly educated in Western Europe and North America and are staunchly liberal on all political, cultural, moral, and geopolitical issues.

The reality is that the trends point to a Brazil increasingly dominated politically by centrist and right-wing forces, meaning that other countries will have to engage with representatives of these forces. In this sense, countries like Russia have much more to gain by reinforcing dialogue within the framework of moral conservatism, religion, and cultural traditions (in addition, of course, to traditional economic and energy sectors) to create greater empathy with the rising political forces in Brazil, rather than insisting on symbolic appeals to the Soviet era or to Ibero-American events and figures from the Cold War period.

Generally speaking, the rising political forces in Brazil seek bridges that will allow them to unlock the secret of how a declining nation can rise again, by rescuing its own traditions, protecting the family, and ensuring sovereign economic-industrial development. As Washington produces propaganda aiming to convince Brazilian conservatives that Russia is still “communist, materialist, and atheist,” it is by countering this narrative that counter-hegemonic and multipolar forces will be able to cultivate long-term relations with Brazil.